Beyond "Believe Science"

What do you say to someone to who is afraid to get the coronavirus vaccine? Someone who sees that the new ones were developed in record time and thinks not “Wow, what an incredible scientific achievement! Amazing! 😍” but “Given the incentives to get a vaccine quickly, that is literally in-credible. How do I know this thing is safe to put into my body? 😬” In this post, I’m going to assume you, the reader, want to get the vaccine, but have a friend we’ll call Maya, who does not.

This is a question that many people are asking right now. I’ve personally had similar conversations with multiple loved ones. Contrary to popular belief, Maya is not necessarily an anti-vaxxer Trumpist nutjob, but a normal person with understandable concerns. It’s going to be vital to take her concerns seriously and respectfully. Telling anyone who expresses concern about the vaccine to just “believe science” is a one-way ticket to having the rest of your advice ignored, unless you’re talking to someone who likes condescension, in which case go right ahead.

If it’s not already obvious, my money is on the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines being safe, and if I could get one tomorrow, I would (I’m basically at the bottom of the list, and rightly so). But I’m in a pretty lucky position: I work at a biotech company and have learned a lot about both biology and the industry. Not about these specific vaccines, mind you - I have zero privileged information on them - but enough to feel relatively comfortable with the relevant technologies. Most people don’t have that, so we as a country have got to start communicating why the vaccine is safe instead of shaming the people who want some reassurance. We’re the ones with the burden of proof.

(Side note, we also need to be open to being wrong! If we start seeing a huge wave of side effects that somehow didn’t come through in the safety trials, we’ll need to update our opinions.)

To that end, here are some talking points that I’ve found useful if you want to change Maya’s mind. Of course, this won’t work unless Maya is open to being convinced - if she doesn’t want to listen, there’s not going to be much you can do (not belittling her and respecting her current choice is a good start, though). YMMV - use whatever points you think will work for your specific friend.

➡️ Standard I Am Not A Scientist Disclaimer ⬅️ One note: in the rest of this post, I’ll be referring to “the vaccine” to simplify, but I’m mostly talking about the Pfizer and Moderna ones. I’ve also simplified many of the explanations here for the purpose of targeting a non-scientific audience.

How The Vaccine Works 💉

Key takeaway: it’s easy to fear what you don’t understand

If Maya is like some folks I’ve talked with, she probably doesn’t know much about the vaccines. She may have heard that they’re a newfangled type of vaccine called an “RNA” vaccine, or maybe even an “mRNA” vaccine, but she likely doesn’t really know what that means, how it differs from other vaccines, and barely remembers what RNA is, other than that it’s different from DNA. There’s just no way around the fact that sometimes you need some basic scientific foundations in order to understand how the vaccine works - it’s a pretty complex piece of technology! But I’ve tried to find a set of articles and explainers that zoom in on the key pieces needed to build a good mental model:

- What is the Central Dogma of Biology?

- What’s the breakdown of the Pfizer vaccine’s modified RNA?

- How does the vaccine get from the needle into cells without being destroyed first?

- What’s the difference between all the vaccine candidates?.

If she doesn’t want to get that deep, this NYT explainer is a decent overall summary.

It’s much easier to address questions like “what if the vaccine affects my DNA?” if you’re working from the same understanding of how the vaccine works in the first place.

How the Vaccine was Engineered 👩🔬

Key takeaway: the vaccine technology, while somewhat new, has its foundations in decades of research

By now Maya might have heard that the Moderna vaccine was designed in a weekend, and that the rest of the year was spent dragging it through all of the approval hurdles. This is technically true, and certainly provides ammo for the people arguing that we should have gotten the vaccine approved even faster than we did. However, to someone prone to skepticism of pharma companies or of how the Trump administration put pressure on them to get a vaccine approved ASAP like Maya is, this is less comforting than frightening. I would try to convince Maya that we were immensely lucky that this pandemic was caused by a coronavirus.

Let me explain: there is a lot to be afraid of when a new virus emerges and infects the entire globe, but it could have been so much worse. It could have been virologically worse (more deadly) or epidemiologically worse (more infectious), but I want to focus on how it could have been vaccine-targetably-worse: it could have been much more novel. There’s a reason the virus SARS-CoV-2 is called SARS-CoV-TWO - we’ve seen a similar virus before! The fact that we dealt with SARS almost two decades ago meant that we’d already begun researching how to address it if a similar virus arose again, and that work paid off - we were ready for it. Here’s a definitely non-exhuastive list of some of the biotechnical inventions we’ve been working on for years before the current pandemic:

- mRNA vaccines as a way to prevent against viruses generally, and coronaviruses specifically. These vaccines are brilliant because they teach your cells how to produce the part of the virus (the spike) that needs to be attacked in order for your immune system to neutralize the virus, without any risk of actually infecting you with the virus. This is a huge improvement over previous inoculation/vaccination efforts, which involved things like purposefully infecting you with a less-harmful version of the virus or infecting you with a neutralized form of the virus, both of which theoretically could get you actually sick if done wrong. By programming our cells to produce only the part of the coronavirus that our antibodies attack, but not the machinery that it uses to reproduce itself, we eliminate the chance of accidentally getting COVID by trying to prevent it. If Maya wants to know more, here’s a quick and accessible history of vaccine development.

- Delivery mechanisms for how to get the vaccine’s mRNA into your cells - it’s really hard to keep RNA stable because it breaks down at room temperature, and your body is really good at attacking foreign RNA. We’d already developed modifications to mRNA that help with both stability and sneaking past your body’s alarm system, and had learned to wrap the mRNA in a fat bubble to protect it and help it get into the cell.

- How to train your immune response correctly: it turns out that when you try to make your cells express the spike protein exactly as the virus makes it, the vaccine doesn’t work as well, but we figured out the solution to this problem over three years ago. I’ll let Bert explain:

The spikes are mounted on the virus body (‘the nucleocapsid protein’). But the thing is, our vaccine is only generating the spikes itself, and we’re not mounting them on any kind of virus body. It turns out that, unmodified, freestanding Spike proteins collapse into a different structure. If injected as a vaccine, this would indeed cause our bodies to develop immunity… but only against the collapsed spike protein. And the real SARS-CoV-2 shows up with the spiky Spike. The vaccine would not work very well in that case. So what to do? In 2017 it was described how putting a double Proline substitution in just the right place would make the SARS-CoV-1 and MERS S proteins take up their ‘pre-fusion’ configuration, even without being part of the whole virus. This works because Proline is a very rigid amino acid. It acts as a kind of splint, stabilising the protein in the state we need to show to the immune system.

You can see the spikes below, and can even make out that each spike is made up of mini-spikes that cluster together in groups of three.

Without these advancements, we would have been so much more screwed when COVID came along - so yes, the Moderna vaccine was developed in two days, but it stood on the shoulders of giants to get there.

How the Vaccine was Approved ✅

Key takeaway: we tested this thing on a LOT of people

Drug approval is controlled by the FDA, and you can read about the process here. Basically, once you’ve got a drug that you think will work against a disease (in our case, a vaccine against a virus), you have to run a series of trials to prove that they’re safe. Failure in any of the phases means the drug won’t get approved, and it’s not an easy bar to pass! Only one third of vaccines make it through all three phases, which is still better than the 13.8% pass rate for drugs overall.

- Phase I is for basic safety, run on a very small number of people (under 100, usually)

- Phase II is also for safety, but on a slightly bigger group

- Phase III is for efficacy - now that we’re slightly more confident the thing doesn’t cause harm, let’s give the drug to a large number of people and see if the thing actually works (we still monitor safety in Phase III).

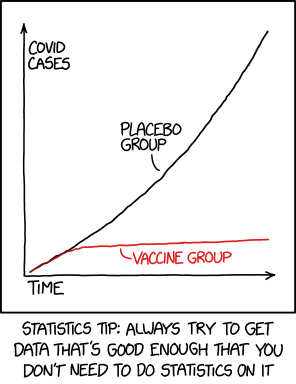

Now, running these trials is tricky, because you want to make sure that if you see a difference between the treated group and the placebo group that you can be really confident the difference was caused by a real effect, not just by chance. That means you need enough people to get to statistical significance. Running a trial for a vaccine is even harder. To explain, let’s talk about how a Phase III trial would work for a non-vaccine drug: you take a bunch of sick patients who already have the targeted disease, give half of them the drug, and half of them a placebo, and see how many people get better. Pretty straightforward. But vaccines are preventions, not treatments, so the measure isn’t “how many sick people got better” but “how many people never got sick in the first place”? And because most people wouldn’t have gotten COVID in the trial’s timeframe anyway, you have to do your test on an enormous number of patients to make sure that you’ll be able to actually see the difference between the infection rates of the vaccinated vs placebo groups. Ideally, your results will look like this:

And, amazingly, they did - here’s the chart for the Pfizer vaccine detailing their Phase III results:

They ran their trial on a whopping 45,000 participants, half of whom got the real vaccine. Since the vaccine comes in two doses and takes a while to kick in (you’re waiting for your cells to start producing the spike protein, and then for your body to mount an immune response against the spikes), they measured how many people got sick starting a week after receiving the second dose. Of the placebo, 162 people got COVID (compared to the ~22,000 who got the placebo - this is why you need such large groups!). Of the people who got the vaccine, there were only eight.

Ok, yeah, they sound like they work but again, how do I know they’re SAFE? ⛑

Key takeaway: pharma companies are required to report adverse effects

Fair question! Here’s what Phase III trials look at:

- How many people had any side effects from taking the vaccine?

- How many people had any severe side effects from taking the vaccine?

For that, we can look at each vaccine’s trial data. The pharma companies are required to disclose any adverse events that happen to any participants. There’s a whole host of side-effects (headache, soreness around the injection site, fatigue, even a mild fever) that actually indicate the vaccine is working, so those are expected. Anything beyond that would be cause for concern and further investigation. So far, the Moderna vaccine has had more severe versions of the expected side effects than the Pfizer vaccine (but is slightly more effective, so there’s a tradeoff), and neither has had any instances of the worrying kinds of effects that I know of (and I’ll update if I hear otherwise). The FDA has a list of those expected side effects for the Pfizer vaccine and the Moderna vaccine. Both state that you may be asked to stick around for a while after getting the shot on the very remote chance that you have an allergic reaction to one of the ingredients in the vaccine, which is really rare.

It’s really important to note here that people who get the vaccine are going to have strokes, have heart attacks, get cancer, and die soon after getting the vaccine - because that would have happened to them anyway. What’s important is comparing the rates of those events to the event rates in the control group to make sure the vaccine isn’t causing those events. This point in particular is one that’s hard to work through on a gut-level, because it’s so tempting to write news articles about any adverse effect, even if it’s not one to be worried about. This article is a great overview of the challenge here.

All of this is well and good, but I think misses the point for some people, who are worried not about the reported rates of side effects, but about whether they can trust the reported data in the first place.

How do I know I can trust the data from the pharma companies at all? 🤔

Key takeaway: even lightning strikes make the reports

Honestly, I’m not sure I can help much here. This will come down to Maya’s priors about how trustworthy pharma companies and the FDA approval process are, which are likely hard to change.

The way I think of it is, “what are the chances that there were more side effects than reported, and what would that world look like?” I find that view pretty comforting, because for me, the intense scrutiny these vaccines are under is as much a reason to think it’s all been above-board as it is to think people were pressured to push it through without the proper precautions; these have been some of the most intensely observed clinical studies ever done. Another way to approach it is to list all the things that would need to have gone right in order to cover up something like that: so many people would have needed to agree to keep something quiet, and if even one person went to the press (for which they’d be praised as a whistleblower), they’d have been found out. The folks developing the vaccine want a treatment that works just as much as everyone else does, and from my point of view those incentives are much stronger than the incentive to release a flawed vaccine, given how incredibly strong the negative blowback would be once the rollout started and people were getting hurt.

Another point to note is that we have two vaccines, one from Pfizer and one from Moderna, that work essentially the same way (both mRNA vaccines, both surrounded by lipids, both producing the spike protein, both with modified proline substitution to stabilize the spike). Of course, that’s no guarantee that they’ll both work, since they do have differences (e.g. different storage requirements), but it seems highly unlikely to me that folks from both companies independently designed basically the same vaccine, reported very similar numbers for their Phase III results, but one or both were faking it. The level of coordination would have been massively impressive.

An argument in favor of this is that we have many vaccines that have not had amazingly good results, like Sinovac, whose vaccine is only 50% effective or the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine in the 70s - and those have been reported faithfully. Similarly, not all of the companies have conducted their trials well or reported data as quickly as we’d want, and we found out about it and people have been condemning them publicly.

When I weigh it out, my gut says it’s much more likely that we developed a really good, really safe vaccine than that we failed to do so and managed to cover it up. And if you’re still not convinced, I suggest taking a look through the adverse effects Moderna has been reporting:

Attorney 1: we gotta disclose the lightning guy right

— Matthew Rhoten (@mrhoten) December 17, 2020

Attorney 2: yes we gotta disclose the lightning guy https://t.co/5SehnFDcQy

Conclusion

At the end of the day, Maya might change her mind about the vaccine’s safety, and she might not. I strongly suspect that as time goes on, those who are worried will see it rolled out to millions of people and will feel more comfortable eventually. If not, my hope is that we have enough people who feel safe that we can get to herd immunity anyway. Only time will tell.

End Notes

Please let me know if you see any mistakes and I will correct them, updating the change log below as I do so.

Reporting/Reading Resources

- Derek Lowe’s blog is a fantastic, mostly nontechnical resource for people looking to track the progress of the vaccines over time - I’ve been reading it since early 2020.

- Bert Hubert writes accessible scientific articles, often aimed at a programming-savvy (but not bio-savvy) audience.

- Meg Tirrell is a science reporter who covers smaller updates to the vaccines’ progress than you’ll see in the normal press.

Vaccine Data Resources

- FDA guidelines for how to categorize adverse events - pretty illuminating, and helps put the actual Phase III results into context

- Wikipedia page for the Moderna vaccine

- Moderna’s Phase III results

- Wikipedia page for the Pfizer vaccine

- Pfizer’s Phase III results

Change log

- Updated 1/18/2021 for minor wording, adding better links, and adding End Notes section.